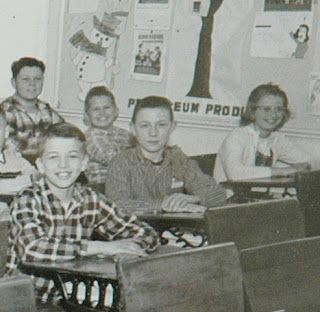

The Erling Rolfsrud family moved to Lake Andrew, south of Alexandria, Minnesota, in the early 50s. Mom and Dad sold the place around 1980. Most of our childhood memories come from this place. The one-room country school we all attended was located at the far lower right margin of the drawing, below, indicated by a small rectangle.

This week, the following article ran in the local newspaper.

A huge housing development is being proposed on the north side of Lake Andrew.

A huge housing development is being proposed on the north side of Lake Andrew.

How huge?

Big enough that over time, in a decade or so, the number of people living there could approach 10,000 – nearly the size Alexandria is now.

Glenwood businessman Larry Zavadil has been planning the project for years, buying his first piece of property in the area about four years ago.

The plan is unlike anything local zoning officials have seen before. “There’s nothing like this anywhere,” noted Tim Schoonhoven of Widseth Smith Nolting and Associates in Alexandria, the engineer for the project.

It encompasses 650 acres of agricultural land that Zavadil has already purchased and could include more property as it moves ahead. He has options on another 350 to 400 acres.

It calls for a mix of uses – affordable housing (in the $90,000 to $120,000 range), assisted living facilities, apartment high rises, single-family lots and a gated community with luxury townhomes.

All totaled, the development easily includes 1,000 units, said City Planner Mike Weber, who has studied the proposal.

It also could include commercial buildings and office space as well.

The Lake Andrew area offers an excellent location – convenience on and off the freeway and close proximity to both Alexandria and Glenwood, Zavadil said in an interview with the newspaper.

With the right infrastructure, Zavadil envisions 9,000 to 10,000 people living in the north Lake Andrew development. “Highway 29 could serve as a mini-freeway,” he added.

Because the scope of the project is so big, it’s hard to even make an educated guess of the total cost. Zavadil estimated the land costs alone will exceed $12 million and putting in streets, curbs, waterlines and other infrastructure could cost twice that much, so the project would be near the $40 million mark without even considering the building costs.

The overriding goal of the entire development, according to Zavadil and Schoonhoven, is to make it as environmentally friendly as possible.

The plan leaves undeveloped open areas that could be used for a city park or “green space.”

Besides protecting woods and wetlands, the plan would preserve 6,000 feet of prime lakeshore. No lots would be built there and the entire stretch would have only one access to the lake, a shared landing that would also include a boathouse.

There’s room enough to put in 40 lots on that part of the shoreline and each lot could sell for about $300,000. So why is Zavadil giving up roughly $12 million in revenue by not developing all of the lakefront lots?

Zavadil, a former member of the Pope County Land and Zoning Committee, said he is tired of seeing developers come in and chop up lakefront land solely for profit without thinking about the long-term benefits to the neighborhood.

“The whole idea is to make the shoreline more of a park and green space so it’s used by more people,” Zavadil said.

Zavadil could have proposed hacking up the lakeshore with lots every 100 feet or so, each with a dock extending out into the shallow, sensitive part of the lake. But he said he wanted to protect the area, not only for the ones who will live there but for future generations as well.

“I thought there’s got to be something better for the lake and its users,” he said. “We should get people off the lakeshore so we don’t have run-off, grass clippings and other issues.”

This resulted in a plan that relies more on a higher density of people living further back from the lake, where they can still enjoy the lake view without each of them having immediate direct access to it, Zavadil noted.

Zavadil said he hopes his development can serve as a template for future lakeshore developments, one that encourages common park areas and beaches and one point of entry into a lake instead of a “whole bunch of docks and boats.”

If everything goes as Zavadil plans, he hopes to start moving dirt within two years.

Weber is impressed with the development’s sensitive approach to the environment.

“This developer has done a wonderful job master planning his site,” Weber said in an interview with the newspaper. “The lake access, the park areas, the open spaces are all thoroughly planned.”

Thanks, Steve and Nancy.

Thanks, Steve and Nancy.

Management group: Back row, Rob Davenport, Mark Weber, Matt McMillan; front, Wayne Kasich, Stan Rolfsrud.

Management group: Back row, Rob Davenport, Mark Weber, Matt McMillan; front, Wayne Kasich, Stan Rolfsrud.

Happily, a neighbor got a good result on her Wednesday cancer surgery, we're all optimistic and continue to cheer for her. A new beginning.

Happily, a neighbor got a good result on her Wednesday cancer surgery, we're all optimistic and continue to cheer for her. A new beginning.

For those of you in to nostalgia and history, here's a photo at Easter, 2005. In case you don't recognize her, look closely, that's Sosie in Sunol talking to Kathleen in the center of the picture.

For those of you in to nostalgia and history, here's a photo at Easter, 2005. In case you don't recognize her, look closely, that's Sosie in Sunol talking to Kathleen in the center of the picture.